Migrating from Vercel to Raspberry Pi 5

· — views

Recently, I decided to migrate this website from Vercel to a self-hosted environment using a Raspberry Pi 5. This transition was driven by several motivations, such as lowering costs and having greater control over the software and hardware that I run.

The Why: Leaving Vercel behind

Don't get me wrong, the developer experience with Vercel is in my opinion second to none. Push code and forget about it, while Vercel automagically deploys your apps. Vercel abstracts all the complicated CI/CD processes behind a nice-looking UI and takes care of everything under the hood.

However, I wanted to explore a more hands-on approach, one that would give me more control over my deployment process and reduce my costs. For this I needed a new home for my website.

The Hardware

The Raspberry Pi 5 seemed like the perfect solution to run my website from. It's a powerful little device, cheap to run and since I'm already running a small media server on another Pi, I was at least somewhat familiar how to set everything up.

I wanted fast and reliable storage so the websites and apps I'm going to deploy would be responsive. I settled on this Geeekpi NVMe adapter and Kingston 500GB NVMe which had sufficient storage capacity for my needs.

Next up I needed a cooling solution and a case for the Raspberry Pi, so I chose the GeeekPi Raspberry Pi 5 Metal Case with Official Active Cooler. The active cooler is low-profile and compatible with the NVMe adapter so it was perfect for keeping the Pi cool.

With a small bit of assembly the Raspberry Pi was ready to go, so now I needed to set up the software.

The Software

The next step was to get the Raspberry Pi up and running with an OS. While there are many Linux distros to choose from, I decided to go with Ubuntu Server 64bit as I wanted to use the Pi in a headless configuration.

Next, I set up and configured SSH to enable me to connect remotely to the Raspberry Pi and continue to configure my new deployment stack.

CasaOS

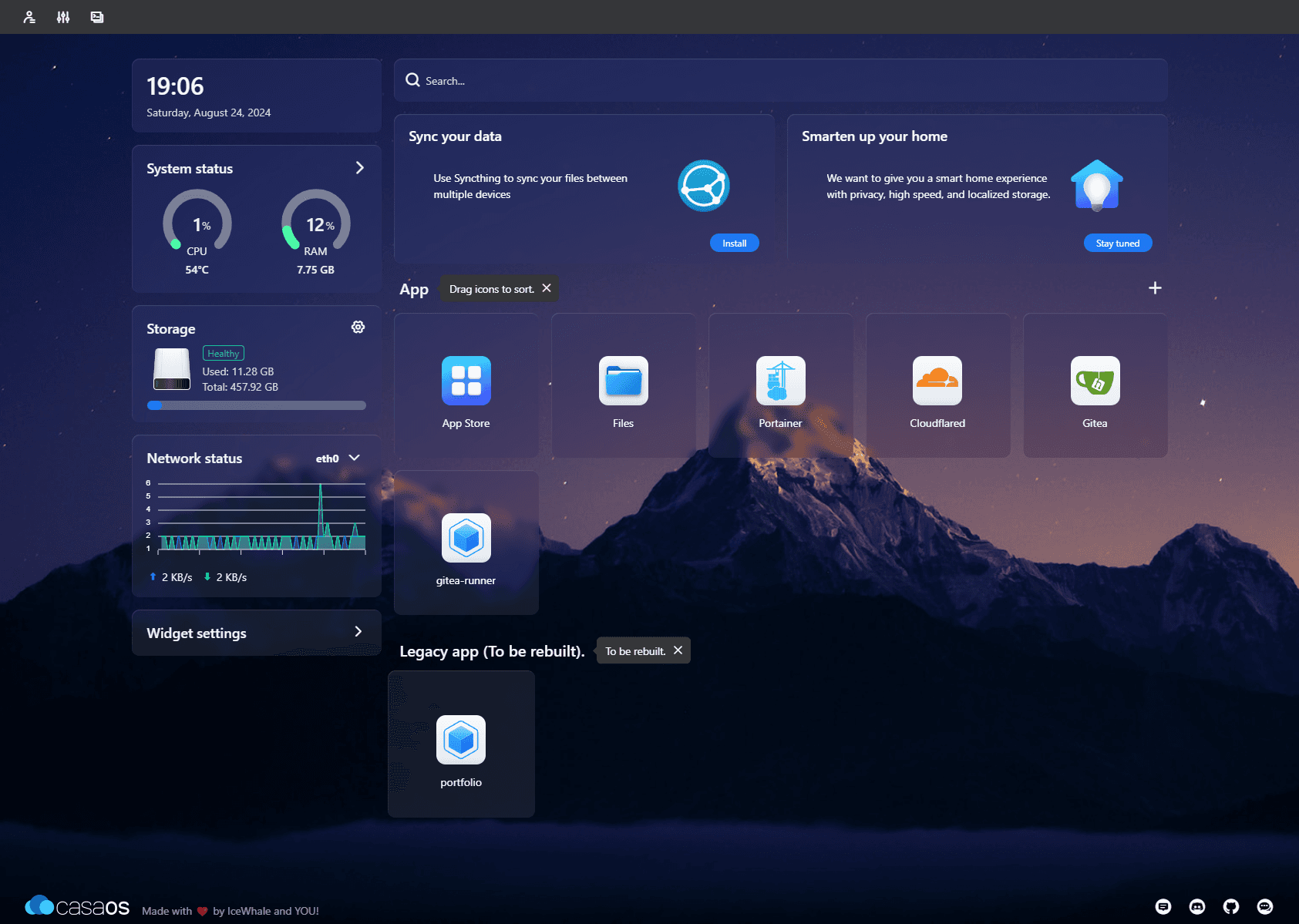

I wanted to manage the Pi from a browser for certain tasks, so I chose CasaOS for this. CasaOS is free and open-source software which takes care of installing Docker and features a nice frontend with an app store for installing other Docker based apps.

I set up CasaOS with a single command — curl -fsSL https://get.casaos.io | sudo bash and within a couple of minutes I was able to access its Apple-like UI where I could access the app store to continue setting up my deployment stack.

Docker

Docker was the obvious choice for containerising my applications. It's a powerful tool that I've used before, although I had no experience with building and deploying my own images. As mentioned CasaOS comes bundled with Docker so there was no extra set up.

With Docker, I could easily build and run containers for my projects, isolating them from each other and making deployment a cinch.

Dockerising my website

With a few additions to the codebase of this website, I was able to completely Dockerise and package it into a distributable image, which could be readily deployed as a container on the Raspberry Pi.

Next, I'll highlight some of the main changes to the codebase which made Dockerising my website possible.

Dockerfile

A Dockerfile is required for building Docker images and should go in the root directory of the project. Next.js has tons of different examples of use cases for their framework, so I borrowed the Dockerfile from this example. This saved me from writing a lot of boilerplate code.

next.config.mjs

Next, I made a small addition to the next.config.mjs. This builds the Next.js app as a standalone app inside the Docker image.

.dockerignore

The .dockerignore file is used for excluding files and directories to keep the final image as lean as possible. In my case I excluded .git, .next and node_modules as these were not required in the final image.

Building the Docker image

With these changes, the last thing to do was to test building the image locally with docker built -t portfolio . this instructs the Docker engine to build the image using the Dockerfile.

Enter Gitea: The Open-Source Alternative

Next, I needed a Git service to host my code. Again GitHub is great and I can't compete with it but this endeavor was all about going open-source and self-hosted. Gitea was on my radar for a while as a great, lightweight alternative to GitHub.

It was easy to set up thanks to CasaOS, and it offered all the core features I needed such as Gitea Actions, which would be essential for my new deployment stack.

Automating deployments with Gitea Actions

One of my primary goals was to automate the deployment process. On Vercel, everything was automated out of the box, but I wanted to replicate that seamless workflow on the Raspberry Pi. Gitea Actions turned out to be just the tool I needed.

With Gitea Actions I could easily define my CI/CD pipelines directly within my repositories. Setting up Gitea Actions involved writing a simple YAML configuration file that would trigger on every push to the main branch.

name: Build And Publish run-name: ${{ gitea.actor }} runs ci pipeline on: [ push ] jobs: BuildAndPublish: runs-on: ubuntu-latest steps: - name: Checkout code uses: https://github.com/actions/checkout@v4 - name: Use Node.js uses: https://github.com/actions/setup-node@v3 with: node-version: '18.17.0' - name: Decrypt secrets run: ./decrypt_secrets.sh env: SECRET_PASSPHRASE: ${{ secrets.SECRET_PASSPHRASE }} - name: Login to Docker Hub uses: docker/login-action@v3 with: username: ${{secrets.DOCKER_HUB_USERNAME}} password: ${{secrets.DOCKER_HUB_PASSWORD}} - name: Set up Docker Buildx uses: https://github.com/docker/setup-buildx-action@v3 with: config-inline: | [registry."docker.io"] mirrors = ["mirror.gcr.io"] - name: Build and push Docker image uses: https://github.com/docker/build-push-action@v6 with: context: . file: ./Dockerfile push: true tags: ${{secrets.DOCKER_HUB_USERNAME}}/${{vars.REPO_NAME}}:v1 - name: Stop and remove old Docker container continue-on-error: true run: | sudo docker stop ${{vars.REPO_NAME}} sudo docker rm ${{vars.REPO_NAME}} - name: Pull new image and start Docker container run: | sudo docker pull ${{secrets.DOCKER_HUB_USERNAME}}/${{vars.REPO_NAME}}:v1 sudo docker run -d --restart unless-stopped --env-file ./.env --name portfolio -p ${{vars.DEPLOY_IP}}:3000:3000 ${{secrets.DOCKER_HUB_USERNAME}}/${{vars.REPO_NAME}}:v1

The script would pull the latest changes, build a Docker image, upload it to the registry, stop and remove the existing container, pull the new image from the registry and finally deploy the container with the new image.

It was very satisfying to push code and watch it go live within a couple of minutes, all running on the Raspberry Pi. However, my website was only visible on the local network at this point.

Wrapping it all up

The final piece of the puzzle was to expose my portfolio website to the Internet, so that it could be seen outside my network. However, I didn't like the idea of port forwarding through my router and exposing my IP address to the world.

I had some experience with Cloudflare Tunnels which allows you to use the Cloudflare network as a proxy to expose your apps to the Internet.

Setting this up was straightforward, I changed the nameservers on my domain name to point to Cloudflare, which allows Cloudflare to create the necessary DNS records to set up the Cloudflare Tunnel.

After waiting for a few minutes for the DNS records to propagate, my website was back up and running again.

Conclusion

Migrating from Vercel to a self-hosted environment on my Raspberry Pi has been a rewarding experience. It taught me a lot about Linux, Docker, Gitea and networking. Most importantly, it's given me complete control over my development and deployment process.

Of course its more work than using a managed service like Vercel, but the trade-offs have been worth it. I’ve learned valuable skills, saved on hosting costs, and enjoyed the satisfaction that comes from running my own server.